| Learn about grant proposals and how to use grants to accomplish your stated purposes, objectives, within your own policies and guidelines. |

-

What is a grant?

-

Why is it worthwhile to write a grant proposal?

-

Who can write a grant proposal?

-

What are the standard components of a grant proposal?

-

How do you prepare a winning grant proposal?

Has your community identified a health problem and a strategy for addressing it, but reached a roadblock to action because of inadequate funding? A grant can provide that much-needed funding and enhance the community's capacity for change.

Whether you have never contemplated writing a grant proposal and feel intimidated about how to begin, or you have written grant proposals in the past but feel a bit rusty and want to enhance your capacity, this is the tool for you! This discussion primarily covers how to apply for grants available through the public sector, but many of the strategies can be applied to foundation grant proposals as well.

What is a grant?

A grant is a sum of money given to an agency or individual to address a problem or need in the community. The written document that one prepares as a means of requesting or applying for this money (funding) is a grant proposal.

Grants are not synonymous with contracts. Organizations or individuals can use grants to accomplish their stated purposes, objectives, within their own policies and guidelines. Contracts are legally binding, and represent an arrangement in which contracting agencies (federal or state government, for example) buy services from organizations or individuals in order to fulfill obligations or responsibilities.

Grant funding is available via both the public and private sectors. In the public sector, money is raised via taxes and other government revenue, and then allocated through legislation to address social issues.

For example, in 1996, the U.S. Congress established an abstinence education program as part of welfare reform legislation. Congress pledged $50 million annually for five years to state administrative agencies, which were then given autonomy to determine programmatic priorities and award community - level funding to entities such as community organizations, local health departments, and faith based organizations.

In the private sector, businesses (e.g., corporations and foundations) and even individuals choose which social issues to address and offer grant awards based on their special interests or research priorities.

Why is it worthwhile to write a grant proposal?

There may be many reasons as to why you want or need to write a grant proposal:

- You want to start a new project (for example, you have identified a need in your community, and documented that no support services or related programs exist to address the need).

- You want to expand an existing project and costs cannot be covered in your current budget (for example, you have a program that serves families living at 150% of the Federal Poverty Level, but you want to expand it to serve families living at 200% of the Federal Poverty Level, thereby increasing enrollment numbers and the need for staffing, supplies, etc.).

- You know of a granting agency that makes awards to pay for the program or initiative that you envision for the need or problem that you have identified.

- You know that you meet the eligibility standards for awards available via grants (for example, some grant awards are limited to educational institutions).

- You are able to commit the time, energy, and other resources needed for the grant-writing process.

- You have been invited to apply for a grant award.

But there are still a couple of things you might want to consider before you get started.

Where can you find Calls for Proposals, Requests for Proposals, Requests for Applications, Notices of Funding Availability, or Program Announcements?

An important note: While all of the suggestions below for finding potential grant sources are still good ones, there have been some changes since this section was originally written. A great deal more information is now available online, and many public funders actually require electronic, rather than paper, submission of grant proposals. The first place to look, generally, is online, using Google to search for something like “grant for [the area in which you’re looking for funding].” An advantage here, in addition to speed and the fact that you’re likely to find several potential funders, is that the websites you find will usually contain a great deal of background information about the funder, names of contact people, clear guidelines for eligibility and proposal writing, and a large amount of other useful information. Searching for grants and submitting proposals online is now probably the best – and preferred – way of finding possible grants.

- The Federal Register is a legal newspaper published daily by the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. It is a great resource for listings of RFPs, RFAs, and Program Announcements.

- State Contracts Registers. While sometimes a little more difficult to locate online, state contracts registers include RFAs for contracts available with government agencies. In a search engine, try entering: "[state name] contracts register". If that search does not yield results, you may need to access funding opportunities more indirectly by going to state government agency home pages.

- The Foundation Center provides an online directory of grant makers, philanthropic news, and other information relevant to finding resources for community programs. The online directory of grants available requires a $9.99 one-month subscription fee for access to thousands of grant opportunities for researchers, students, artists, and other individuals.

- Websites for individual government agencies and foundations

- Special regional centers with walk-in libraries such as Associated Grantmakers, with offices in major U.S. cities

- Notices in a specialized newsletter within your field

And, if the aforementioned resources still don't yield what you are looking for, you can always ask around. Talk with colleagues locally and nationally and with other people you know who have grant writing experience.

What is a typical proposal timeline?

A grant proposal is often a labor-intensive undertaking that requires a commitment of resources devoted to producing a document as long as 15 - 50 pages or more in a relatively short period of time. When a Request for Proposals is released by an agency, the deadline for proposal submission is often as little as one month away. So be prepared to work hard on the development of a grant proposal, keeping in mind that the hard work is finite – only a few weeks – for potentially multiple years of funding to address your identified problem or need.

Who can write a grant proposal?

You can! Do not be intimidated by Request for Proposal (RFP) rules and instructions. Simply read the RFP carefully. You might want to make a plan to stay organized. Highlight key or essential elements (such as the deadline for submission, mailing address, number of copies to be submitted, etc.) as you read through the RFP. You might also find a one-page checklist of all required items within an RFP. If you are intimidated by the writing element, solicit the help of a colleague or someone collaborating in your effort to secure funding. You can also contact the agency soliciting grant proposals and request some samples of previously funded proposals.

You do not need an English degree to put together an effective proposal. While grammar, spelling, and cohesion are certainly important elements of a well-written proposal, substantive elements (such as identifying the need for funding for your topic or population of interest) are ones in which you can be creative in how you present the information. In fact, innovative or creative approaches can enhance a grant proposal's likelihood of success!

At the same time, because readers often have to wade through a large number of proposals, a well-written one often can receive more attention and even a higher rating. If there are no good writers within your organization, find someone who is willing to edit your proposal and turn it into elegant prose. Readers will thank you, and you may well be rewarded for your extra effort.

What are the standard components of a grant proposal?

While some Requests for Proposals may include unique requirements that you must read carefully and follow, many grant proposals follow a similar structure. The most common eight elements are listed below.

The discussion that follows will give you guidelines, one element at a time.

- Cover letter, title page, and abstract

- Statement of the Problem / Needs Statement

- Project Description (goals and objectives and methods / activities)

- Evaluation Plan

- Budget Request and Budget Justification

- Applicant Qualifications

- Future Funding Plans / Plans for Sustainability

- Appendices

Cover letter, title page, and abstract

Instructions for the cover letter and title page will be included with the RFP. The cover letter should be on agency stationery and signed by the appropriate organizational official.

The cover letter – usually limited to one page – should:

- Describe the agency's interest and capacity to successfully implement the proposed project

- Have an upbeat tone that makes it stand out in a positive way

- Summarize the project

- Designate a contact person for any questions about the project

Once again, a well-written letter is likely to get you extra points in the reader’s mind. Make absolutely certain that all your spelling and grammar is correct. There’s often an assumption on the part of the reader or the agency – and it’s often true – that if you don’t take care in writing your cover letter and proposal, you won’t take care running your program, either.

Typical title page contents include:

- Project title

- Name of the agency submitting the grant

- Agency address

- Name of the prospective funder

- Beginning and ending project dates

- The total amount requested

Some RFPs may require a letter of intent that precedes the submission of a grant proposal. These can be challenging to write, as they are basically an abstract of the proposal. Therefore, it is helpful to have a clear purpose, identified need, and some idea as to your strategy for addressing that need ahead of time. You should really have those things in mind anyway as you conduct research for RFPs so you can identify which agency missions and grant opportunities match your interests.

An abstract is related to, but different from, the letter of intent. The abstract includes a summary of the statement of the problem / need, overarching goals of the proposed project (but not the detailed objectives), a summary of the methods that will be used to implement and evaluate the project, and a final paragraph describing your group's or agency's capacity (expertise and resources) for carrying out the proposed project. An RFP may include a limitation on the number of pages that an abstract can be, but a good rule of thumb is no more than two pages.

Statement of the Problem / Needs Statement

The needs statement may be one of the most powerful components of your grant proposal. This is where you really grab the reviewer's attention and make your case for the need for funding. So, do your homework before writing this section. Know your community (e.g., demographic and socioeconomic characteristics within the population), the extent of the problem, and whether or not any previous or existing efforts have targeted the same problem.

Your problem or needs statement should accomplish the following:

- Document the problem you want to address (use text, statistics, and graphs / charts)

- Describe the causes of the problem or the circumstances creating the need

- Identify approaches or solutions attempted to date, based on a review of the literature when possible

Use existing data sources when possible to document the problem. For instance, you might consider using census data for your county, or other existing sources for your area that provide indicators of the behaviors or outcomes you are addressing. If you locate existing county level data, it is also good to research comparable data at the state and local levels, because your argument that the current situation in your area is a problem will be more effective if you present it in relative terms.

For example, instead of stating, "Only 10% of sexually active adolescents in Troubled County report using a condom in the past three months," re-framing the information in relation to state and national data can have a bigger impact: "Only 10% of sexually active adolescents in Troubled County report using a condom in the past three months, while the rate is 15% at the state level and 25% at the national level."

The Internet is an efficient way to research existing state and federal data for you to compare with your local level data, allowing you to:

- Locate census data (data collected every ten years, most recently in 2000, from over 115 million housing units across the U.S., including geographic, demographic, and socioeconomic information) from the U.S. Census Bureau

- Research numerous state and national statistics about women, infants, children, adolescents, and children with special health care needs at the Title V Information System website of the federal Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration.

- Access the full range of Federal Government statistical information available to the public, with links to 70 federal data sources at FedStats.

If you cannot locate existing local data for your needs / problem statement, you may need to conduct qualitative research (telephone interviews, focus groups, or self-administered surveys).

For example, your community may have experienced a lot of growth in population and housing developments in the past five years. With that growth, traffic flow near schools would increase and become more dangerous. In this situation, you might have an intuitive awareness of a need for more cross walks for students / pedestrians, but you do not have a concrete source of data to substantiate this need. Therefore, you can interview school administrators, parents, subdivision residents, and students as a means of documenting the problem.

Finally, as you research the approaches or solutions that have been implemented to date, think about whether your grant proposal will be building upon existing efforts, introducing a unique strategy, or some combination of both. Some reviewers may be searching for that fresh, innovative approach to a problem that has been well documented but not yet addressed effectively.

There is no right or wrong way to present the information within the standard grant proposal sections as long as it is in a logical order that is easy to read. Just remember that your grant proposal is your first opportunity to effectively communicate the need for funding for your special interest or population to a specific foundation or other agency, so make it count. You want to keep the reviewer interested enough to read on and learn more about your important ideas.

If the addition of tables or graphs will make your needs statement more persuasive, definitely include them. Here are some things to consider as you prepare graphic illustrations of your data:

Tips for Presenting Data:

- Use comparative statistics whenever possible (e.g., county vs. state vs. federal, or multiple age groups or ethnicities)

- When determining which type of chart or graph to make, do not use a pie chart if you have more than three or four categories of data

- Use line graphs to show a long-term trend in data

- Use bar charts to depict differences, especially when you are comparing only two categories of data (e.g., only two race/ethnicity categories, male versus female, county versus state)

- Include a chart title that accurately yet succinctly describes the image, and include the year(s) from which the data came

- Always clearly label the y (vertical) and x (horizontal) axes of your charts, and identify the units of measure (e.g., rate versus count)

- Provide a legend to explain data categories, data ranges or intervals, color-coding, etc.

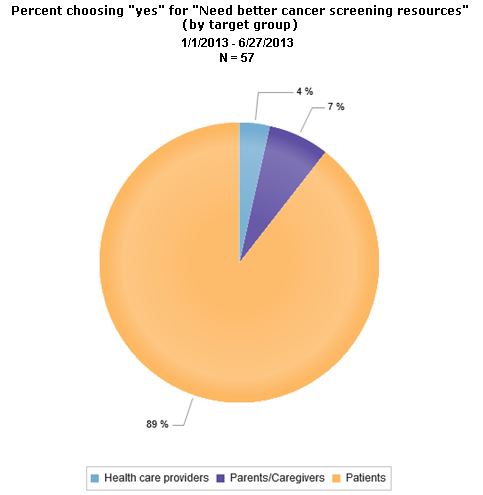

Figure 1: Example Pie Chart

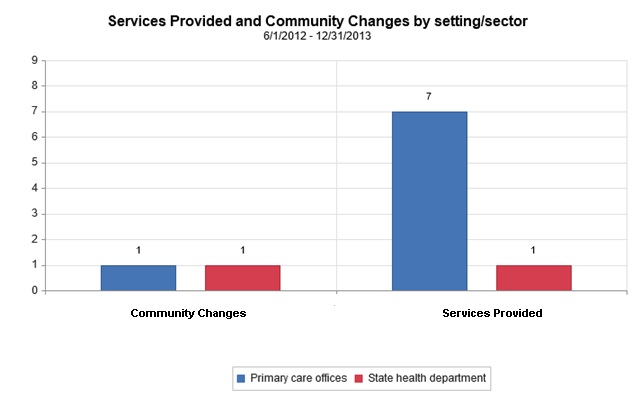

Figure 2: Example Bar Chart

Project Description

Once you have captured the attention of the reviewers by clearly and effectively documenting the need for funding, you get to present the details of how you plan to implement your program. This section of your proposal should guide the reviewer step by step through all activities needed to accomplish your goal(s) in a way that will continue to engage the reviewer's interest and excitement. Furthermore, you will refer to it time and time again over the course of program implementation. Even if program staff changes over time, the project description should provide a road map for anyone to understand and follow.

The project description includes three main pieces of information:

- Goals and objectives

- Methods or activities for addressing the identified problem or need

- A time line chart for the completion of each activity

Goals and Objectives

Goals and Objectives are a very important piece of your grant proposal. Goals are broad statements with a long-term, ideal outcome in mind. Most proposals do not have more than three goals.

Example Goal: "Eliminate disparity among Medicaid enrollees' and privately insured consumers' use of prenatal care in Fertile County."

For each goal, you might develop numerous, corresponding objectives. Objectives are specific statements that will indicate to the reviewer exactly how you plan to achieve your goals. The best objectives have several characteristics in common.

Well-written objectives are:

- Specific. That is, they tell how much (e.g., 40 %) of what is to be achieved (e.g., what behavior of whom or what outcome) by when (e.g., by 2014).

- Measurable. Information concerning the objective can be collected, detected, or obtained from records (at least potentially).

- Achievable. Not only are the objectives themselves possible, it is likely that your organization will be able to pull them off.

- Relevant to the mission. Your organization has a clear understanding of how these objectives fit in with the overall vision and mission of the group.

- Timed. Your organization has developed a timeline (a portion of which is made clear in the objectives) by which they will be achieved.

- Challenging. They stretch the group to set its aims on significant improvements that are important to members of the community.

Do not be discouraged if you find it difficult to write objectives that meet each and every one of the criteria listed above. Like most things in life, writing objectives becomes easier the more you practice!

Building on the example goal of eliminating disparity among Medicaid enrollees' and privately insured consumers' use of prenatal care in Fertile County, below are two examples of how a related objective might be written.

Insufficient Example Objective: "Survey Medicaid enrollees and privately insured clients about why they do or do not access prenatal care services early in pregnancy."

The example above is insufficient because:

- It is not measurable or specific

- It is not timed

Better Sample Objective: "By June 2014, survey 50 postpartum Medicaid enrollees and 50 privately insured clients prior to discharge from the hospital regarding why they did or did not access prenatal care services in the first trimester of pregnancy."

Let's break down the sample above and determine why it is a better objective:

- It is specific - 50 postpartum Medicaid enrollees and 50 privately insured clients will be surveyed prior to discharge from the hospital.

- It is measurable - information can be collected because it will be collected in person (unless patients do not give their consent to participate).

- It is achievable - 100 women is probably a realistic number of people to interview.

- It is relevant - relevant to the mission within the sample goal of eliminating disparities in use of prenatal care

- It is timed - all surveys will be completed by June 2014.

Once you feel comfortable drafting objectives, you should determine whether or not they are "process" versus "outcome" objectives.

A process objective measures the accomplishment of tasks completed as part of the implementation of a program.

Example Process Objective: "By June 2014, distribute 500 copies of the patient education pamphlet, 'Heart Disease Prevention' to men between the ages of 30 and 50 in Coronary County."

An outcome objective measures long term results or impact of a program. Using the same scenario in the process objective example above, an outcome objective might be:

Example Outcome Objective: "By June 2014, decrease the number of men between the ages of 30 and 50 with high blood pressure in Coronary County by 5% from the 2010 rate of 40%."

Methods

You will have a sense of clarity and specificity after drafting your proposal objectives. The next step in the proposal writing process will be to break down each objective into a series of activities needed to achieve it. The methods section describes in detail how you propose to carry out your goals and objectives over the course of a project.

Let's continue using the Coronary County example. You have a process objective for distributing 500 copies of the patient education pamphlet, "Heart Disease Prevention" to men between the ages of 30 and 50 in Coronary County. In the Methods section, you need to show reviewers that you have carefully considered the steps necessary for planning and implementing this objective.

Activities and other details to discuss might include:

- Will you be using an existing pamphlet? If yes, briefly describe it, the credibility of the organization that developed it, and include a copy in your appendices.

- Do you need to develop the pamphlet? If yes, discuss who will be involved. An advisory board? Special committee? Consultants? Include their CVs in the appendices.

- Will the pamphlet be translated for bi-lingual distribution?

- How will you print, copy, and market the pamphlet (if applicable)?

- How will you reach your target population? Via physicians' offices? If yes, include a discussion about how you plan to solicit and involve local physicians in your effort. If no, describe all venues for distribution (Libraries? Grocery stores? Health clubs? Barber shops?).

- How will you document how many pamphlets have been distributed, and which staff will be responsible for that?

When writing the methods section, be sure to:

- Keep the sequential order of tasks in mind

- Make sure that the activities described are cohesive so reviewers see that you know how all pieces of the puzzle fit into the "big picture"

- Include a flow chart of the sequence of events - if applicable to your situation - in addition to a time line chart, which is usually required

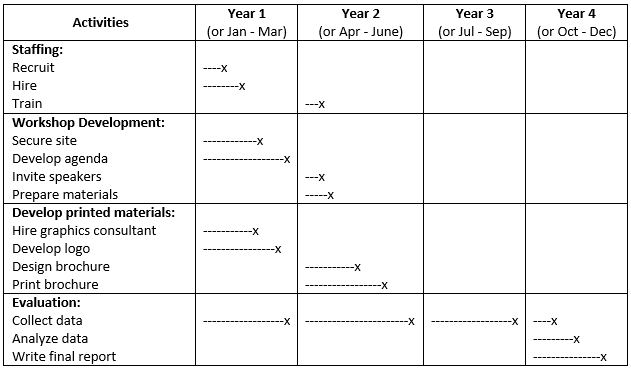

Figure 3: Example Time Line Chart

A commonly used tool is the time line chart (GANTT chart). This chart is used to present a detailed list of all activities and their projected date of completion. Activities are usually listed in sequential order.

You may be applying for only a one-year grant, in which case your time line columns could be representative of quarterly progress versus years, as shown in the column headers in Figure 3 above.

Tips for filling in a timeline chart:

- Try to anticipate every activity an objective might entail and estimate at which point in the program's time frame the activity will be completed

- Understand that the timeline is meant to be used for planning purposes and may be revised over time. For example, some activities will be dependent upon the completion of prior activities. One cannot train staff members until the staff is hired; if the hiring process takes four months versus two, the training timeline will also need to be adjusted.

- It is fine to show multiple items with the same completion date

- Remember that all activities in the timeline will shape your budget request

Evaluation Plan

The purpose of the evaluation plan is to show how you will measure the completion or success of process and outcome objectives. Be sure that your plan includes details about how information will be collected and analyzed. Also describe how and when evaluation findings will be shared with the funder.

How and why is a program evaluation plan useful in a grant proposal?

From your perspective:

- The evaluation plan may help you clarify objectives so they are measurable

- Evaluation helps you continually refine or revise program approaches in future years of funding

- Evaluation data provide information about the relative costs and effort for tasks so activity and budget adjustments can be made in future years of funding

- Evaluation plans are usually required, and will be worth a specified number of points in the rating system when the proposal is reviewed

From the funder's perspective:

- The funder will be able to clearly see whether or not objectives have been met

- The funder will be able to determine whether funds were used appropriately

- The funder will be able to assess whether or not the program's benefits (e.g., outcomes) justify the cost of implementation

There are two main types of evaluation: process and outcome. Your project will dictate which type of evaluation you use. Most likely, you will use a combination of both approaches depending on the types of objectives you draft. Process evaluation assesses the implementation of a program, emphasizing activities to be completed (for example, "distribute 500 copies of a flyer"). Outcome evaluation assesses the short or long-term impact of a program.

Example Process Evaluation: "By June 2004, distribute 500 copies of the patient education pamphlet, "Heart Disease Prevention" to men between the ages of 30 and 50 in Coronary County."

This objective might be evaluated as

- Not accomplished

- Partially accomplished (e.g., only 200 copies were distributed)

- Accomplished

- Exceeded (maybe 600 copies were distributed)

Documentation of this objective should be straightforward, but it is surprising how difficult it can be to get health care facilities and staff to adopt a new data collection form or task and assure that those who interact with patients are recording data consistently and correctly. So, as part of your evaluation plan, you would need to design a system that would yield appropriate documentation of the distribution of the pamphlets. Remember, too, that the system needs to be "user friendly" so staff will use and follow it.

Now, let's look at how you might evaluate an Outcome Objective.

Example Outcome Evaluation: "By June 2006, decrease the number of men between the ages of 30 and 50 in Coronary County with high blood pressure by 5% from the 2003 rate of 40%."

The most important thing to remember about outcome measures with this structure is that you should already have baseline data – current statistics that describe the percentage of men between the ages of 30 - 50 with high blood pressure living in Coronary County. This is important for two reasons:

- The fact that you are including the objective in your proposal means that you should have data to back up the need to address it. The data would be most appropriately described in the Statement of Problem / Need.

- When you evaluate the impact of your program, you will re-measure (or research statistics in an existing surveillance system) the percentage of men between the ages of 30 - 50 with high blood pressure living in Coronary County, in order to compare pre- and post-program high blood pressure statistics.

Let's assume that you assess the percentage of 30-50 year old men with high blood pressure before you implement your program, then three years later. You find a 4% decrease after three years. Can you automatically attribute that decrease to your program? If only it were that easy! Other factors such as competing programs may have been solely responsible for the percentage change, or may have indirectly enhanced the impact of your program.

For example, let's say a different community-based organization in Coronary County received a grant in the same year that you did. The other program targeted men ages 20 - 40 with education about the importance of daily cardiovascular exercise. 50% of the men exposed to that intervention adopted a regimen of 20 minutes of cardiovascular exercise three times per week. Those same men are part of your evaluation sample three years after you implement your program.

One purpose of your evaluation would be to determine whether or not the percentage of men ages 30 - 50 with high blood pressure decreased because you educated men about ways to prevent heart disease, or because half of the men who participated in another program adopted a regular exercise regimen.

Evaluations can be complex, time-intensive aspects of a program. Unless you can afford to budget for an evaluation consultant, design the evaluation plan within the strengths and limitations of program and staff resources.

Budget Request and Budget Justification

Once you have drafted the detailed information for your goals and objectives, methods, and evaluation plan, you will have the foundation for your budget request. You will now need to assign corresponding dollar amounts to staff positions and activities.

Common budget line items for the Budget Request include (details for each are provided below):

- Staff salaries

- Taxes

- Fringe benefits

- Indirect costs

- In kind items

- Rent and utilities

- Equipment and supplies

- Postage

- Travel

Staff salaries

Staff salaries are listed in a budget as FTEs, or "Full Time Equivalents." A person working a 40-hour week will be listed at 1.00 FTE, and the actual amount for salary requested in the budget will be 100% of the proposed salary for that position. A person working 20 hours a week will be listed at .5 FTE, and the actual amount for salary requested in the budget will be 50% of the proposed salary for that position.

| Staff Position | Full Time Salary | FTE | Year One Budget Request |

| Project Director | $55,000 | 1.0 | $55,000 |

| Project Assistant | $35,000 | 1.0 | $35,000 |

| Administrative Assistant | $25,000 | .5 | $12,500 |

Fringe benefits

Fringe benefits may include half an employee's social security and Medicare payments (public agencies are exempt) and voluntary benefits such as medical, dental, disability, life insurance, and retirement plans. These are generally calculated as a percentage of staff salaries.

Indirect costs

Otherwise known as overhead, indirect costs are defined as an attempt to compensate the organization for the cost of housing a project. Indirect costs may or may not be provided by your funding agency. They are often allocated as a fixed percentage of your direct costs.

In-kind items

An in-kind line item will not add any costs to the project because it is paid for or absorbed by the agency applying for the grant. In kind services might include paying for rent (perhaps a separate grant within the agency already covers this, so the agency can afford to not request rent as a line item of the budget in the new grant proposal). Or, perhaps clerical / administrative staff are shared across multiple grants in-house, so a proportion of an administrative staff person's time will be listed as "in kind" in the budget line items.

In the Budget Justification, be sure to clearly describe the need for each line item total requested. In one or two sentences per budget line item, show the reviewer exactly how you arrived at the total for an item.

Example Budget Justification for a travel line item of $2115: The Project Director will present project findings at a total of three national conferences in year two of the project. Airfare will average $400 per trip; hotels will average $100 per night; and the per diem (allowance for meals) will be $35. For three trips averaging three days and two nights each, the total request for travel is $2115 [$1200 airfare, $315 food, and $600 hotel].

Some tips to consider when making your budget:

- Make sure that your budget does not exceed the maximum amount stated in the request for proposal (RFP)

- Make sure that the numbers in the proposal narrative and budget justification text match those in the line item budget

- If you are required to submit budget projections for multiple years, remember to include a cost of living raise in staff salaries and allow for inflation among supplies, utilities, etc.

- If you are inexperienced with a proposed activity (such as conducting focus groups), talk with someone who has done this to gain insight as to how much to budget for. You may learn about costs that you did not anticipate. It is better to discover those before you submit your grant proposal than after you are working within a set budget that could require that you reduce the total number of activities or exclude some altogether.

For example, say you have proposed to conduct three focus groups with low-income parents of children with special health care needs (ages 0 - 3) in your county over the next 6 months. Here are some things you might need to consider as you calculate your budget request:

- How will you solicit participation in the focus groups? What printing, outreach, or marketing costs will you incur?

- How many parents will participate in each focus group?

- Will parents need assistance with transportation to the focus group site?

- Will you offer an incentive (e.g., money or on-site child care during the sessions) for focus group participation?

- Will you serve food / beverages during the focus group session?

- Will you moderate focus groups, or pay a professional social researcher?

- Will you need a bi-lingual moderator? If yes, will this be an additional expense or do you have existing staff resources?

- Who will record / transcribe the focus groups? Will you need to pay for this service?

Of course, this list is not exhaustive, but you can see how one proposed activity has many planning and implementation details tied to it. And each detail potentially increases the amount of money that you need to request in your line item budget.

Applicant Qualifications

Use this section of your proposal to convince the reviewers why you should be funded rather than someone else. You may be requesting funding for a problem or need that is already well documented. While reviewers may need no convincing that the issue is important, timely, etc., they have a limited amount of funds to award. What makes your qualifications and your approach or strategy better than the competitor's?

You should onclude the following information in this section of the proposal:

- Describe your agency's (or your) mission, history, and existing experience.

- Emphasize agency strengths and current contributions to the field or community in the topic area for which you are requesting funding.

- Highlight links to community collaborators and other resources. Obtain letters of support (or letters of participation) for the proposal appendices from the same collaborators you mention in this section.

Future Funding Plans / Plans for Sustainability

Federal or state agencies often want to see a long-term plan for the self-sustainability of a project. The reasons for this vary. Maybe funding at the federal or state level will only be available for a couple of years. Maybe funding for a special interest will only be available until elections bring in new legislators with different fiscal and policy priorities. Some programs require a match of funding from the beginning. For example, for every four dollars awarded, a grantee (you) may be required to contribute matching funds of two dollars. Funders will want to know how grantees' matching funds will be provided and sustained.

Some initiatives will need to be in place for years to come if they are to have a long-term impact on outcomes such as health status indicators.

For example, you cannot expect to get 25% of smokers to quit smoking within a two-year grant cycle, but perhaps after a decade of persistent programming, smoking rates will drop substantially. Therefore, if a foundation or other agency can only afford to fund this particular issue for two years, it may want to know how you plan to continue tobacco use prevention efforts in your community over the long term.

While you cannot guarantee that your proposed program will be self-sustainable, it is important to make your best case for sustainability and describe a plan.

Some things to consider:

- Will you be able to charge a fee for services provided?

- Can you market and sell any materials developed via the proposed funding?

- Will you institute membership dues (when applicable)?

- Can you develop new grants or contracts for funding?

If the answers to these questions are "yes", discuss the strategy and time line for establishing the revenue-generating component of the project. As a rule of thumb, most projects rely entirely on the funding source in year one, as this is the year that planning and implementation activities are accomplished. But by year two, you may be able to include some revenue-generating activities in your time line.

Appendices

Appendices are supplemental materials that do not belong in the body of the proposal, but nevertheless are important pieces of information, such as:

- A marketing or dissemination plan schematic

- A project staffing flow chart

- A time line chart of proposed activities (you might include this in the body of the proposal instead of or in addition to here)

- An evaluation instrument (e.g., a survey that will be used)

- Any existing educational or printed materials to be used

- Biosketches or curriculum vitae of key project personnel, including Advisory Board members and any consultants already identified

- Letters of support and/or participation

One-page letters of support / participation should be submitted on official letterhead from each agency that you have proposed as a collaborator. Letters should be signed by an Executive Director or Chief Executive Officer of the collaborating or supporting agency. You may want to draft the letters for each collaborator (in fact, they may request that you do this), but make sure that each letter is unique to your working relationship and shared interests. Highlight the significance of the proposed collaborative relationship in the context of proposal goals and objectives. Also summarize your and your collaborating agency's capacity and strengths for addressing the problem or need identified in the proposal.

How do you prepare a winning grant proposal?

In these times of shrinking state budgets, the numbers of grant proposals submitted far outweigh the number of grants available. Organizational and community leaders seeking funding for special interests or populations must therefore prepare grant proposals that are superior to their competitors'. Still, you should keep in mind that even if you and/or your collaborators prepare the best proposal possible, it might not be accepted. Do not be discouraged. One source notes that 50% of proposals funded are resubmissions that were denied the first time.

So, once you have identified a need or problem within your community, done your homework and documented the problem, and presented a credible and persuasive strategy for addressing the need or problem, what else can you do to ensure that your grant proposal is "top notch"? Listed below are some things to consider as you complete the final, comprehensive review of your draft proposal.

"Star Proposals": What Features Shine in the Eyes of the Reviewers?

- Following all directions

- Well-organized proposal sections that are integrated and easy to comprehend (for example, a clear table of contents, nice layout and graphics, etc.)

- Well researched and documented statement of the problem (provide narrative and statistical detail, and reinforce the message with graphs or charts to persuade the reviewer)

- Statement of the problem or need in a way that explicitly addresses the funder's priorities

- Creative or innovative strategies for addressing the need / problem

- Feasible goals and objectives (e.g., "Decrease by 2% the number of adolescents ages 15-17 who report cigarette smoking over two years" as opposed to, "Decrease by 50% the number of adolescents ages 15-17 who report cigarette smoking over two years")

- Measurable objectives (e.g., "Implement a five minute provider-patient education protocol for heart disease prevention for primary care visits among men ages 30 - 50 in Coronary County from January 2004 - January 2005" as opposed to, "Educate men in Coronary County about the risk of heart disease")

- A sound evaluation plan. Have you shown that you have the capacity to access primary data [data that you collect via interviews, surveys, or focus groups] or secondary data [existing data such as census data]? Have you clearly indicated whether or not you will be evaluating implementation versus short- versus long-term outcomes, or all three? Have you allocated a proportion of the budget line items for evaluation?

"Snoozers and Losers": Why Grant Reviewers Need A LOT of Coffee

- Not following directions. Pay attention to funder criteria regarding margins, text spacing, and single- versus double-sided pages, bound versus stapled, etc.

- Spelling and grammatical errors. Spell check is a great tool, but it shouldn't be a substitute for checking your work yourself, and having someone else read through it to make sure that not only are all words correctly spelled and correctly used, (e.g., there versus their), but that your writing is concise, with clear transitions and good organization. Once again, if there’s no one in your organization who can write or edit well enough to make sure that the proposal is grammatical and well-organized, find someone who can to help you. It’s important enough to take some pains to get it right.

- No previous experience with work in the area of the identified need / problem

- Lack of community involvement in the planning process

- Overall lack of focus - maybe the proposed intervention is too broad for the issue at hand

- Inappropriate strategy given the problem or target population

- Unrealistic timeline for accomplishing proposed activities

- Weak evaluation plan

- Unrealistic budget, or one that does not clearly justify how the requested funding will be spent

- Lack of potential for the program to become self-sustainable (when applicable)

- Poor organization throughout the proposal. Make sure that all sections are cohesive and complementary.

In Summary

A grant is a sum of money given to an agency or individual to address a problem or need in the community. The written document that one prepares as a means of requesting or applying for this money (funding) is a grant proposal.

A grant proposal is a labor-intensive undertaking that requires a commitment of resources devoted to producing a long document in a relatively short period of time.

Read RFP rules and instructions carefully. Make a plan to stay organized, noting essential pieces of information (such as the deadline for submission, mailing address, number of copies to be submitted, etc.).

If you are intimidated by the writing element or do not want to manage it alone, solicit the help of a colleague or someone collaborating in your effort to secure funding. If you write as part of a team, assign tasks and sections of the proposal.

Common elements in a grant proposal:

- Cover letter, title page, and abstract

- Statement of the Problem / Needs Statement

- Project Description (goals and objectives and methods / activities)

- Evaluation Plan

- Budget Request and Budget Justification

- Applicant Qualifications

- Future Funding Plans / Plans for Sustainability

Appendices, which often include:

- A marketing or dissemination plan schematic

- A project staffing flow chart

- A time line chart of proposed activities

- An evaluation instrument (e.g., a survey that will be used)

- Any existing educational or printed materials to be used

- Biosketches or curriculum vitae of key project personnel, including Advisory Board members and any consultants already identified

- Letters of Support / Participation

Features of a strong proposal that enhance the likelihood of funding:

- Well organized proposal sections

- Well researched and documented statement of the problem

- Creative or innovative strategies for addressing the need / problem

- Feasible goals and objectives

- Measurable objectives

- A sound evaluation plan

Online Resources

Guidelines for grant writing from the Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance address preparation for and writing of a grant.

The Foundation Center provides an online directory of grantmakers (by subscription), philanthropy news, and other information relevant to finding resources for community programs.

The Grantsmanship Center provides information about federal, state, community and international funders.

The Internet Nonprofit Center publishes the Nonprofit FAQ, a resource of information provided by participants in online discussions about nonprofits and their work. Grants and grant writing are just one of the categories. You can join the nonprofit discussion list through the site or go to Nonprofit Info Page.

Non-Profit Expert.com provides fundraising and grant writing information.

Ohio Literacy Resource center provides links to grant writing information and funding information on the Internet.

Philanthropy Journal Online is an electronic publication of the Philanthropy Journal of North Carolina. Its searchable site offers news on fundraising, volunteers, foundations, and more.

The Virtual Foundation is an online philanthropy program that supports grassroots initiatives around the world. Screened projects are posted on the website where they can be read and funded by online donors.

Print Resources

Coley, S. & Scheinberg, C. (1990). Proposal Writing. Sage Publications, Inc., Newbury Park, CA.

Hall-Ellis, S. et al, (edited) by Hoffman, F. (1999). Grantsmanship for Small Libraries and School Media Centers. Libraries Unlimited, Englewood, CO.