| Understand the nature of mercy, and how to expand one’s awareness and actions regarding merciful behaviors in community life. |

This and other sections in the Tool Box chapter on Spirituality and Community Building (Chapter 28) have been written with the support and contributions of experts connected with the Charter for Compassion. For more information about the Charter and its work, visit www.charterforcompassion.org.

“It is a sword that heals.”

Dr. Martin Luther King promoted nonviolent action as a powerful and just weapon, which cuts without wounding and ennobles those who wield it to enact mercy.

Mercy is our most powerful weapon for peace and justice.

This Community Tool Box section about mercy draws from science and academia, inspiring role models, cultural wisdom traditions, the arts, and our experiences as an interfaith minister and holistic physician active in the compassion movement. The authors write this section using the first person plural, including ourselves in all humanity. We mean to invite readers to consider the concept of mercy as though reading through our collective human vision. “We,” “our,” and “us” are chosen to remind readers that we all have the capacity as humans, separately as well as together, to recognize needs and act with compassion.

We dedicate this writing to the many hardworking people in community who are inspired to act from compassion.

Introduction

Mercy is a natural human quality that is highly relevant to our lives and community work. It is a practical and effective way to relate to one another toward alleviating pain, with peace and justice. The conscious welcoming of mercy arises from within ourselves and reaches other people as practical, useful actions that relieve suffering. We apply the virtues of mercy in our community-building work and in our daily lives by seeking to understand, having compassion, and directing our actions to serve others as best we can.

Mercy is a human capacity to access understanding from opposite perspectives, feel both forgiveness and remorse, and move with the urge to relieve pain.

Mercy Is Practical

Mercy is about making right from wrong and fixing problems to the benefit of everyone involved. In any situation, especially when people have been or are being injured, we offer tools and skills to improve chances for a merciful outcome. This section is full of practical tips to seek and attain mercy, wherever we are, through understanding, forgiveness, and accountability.

Mercy Is a Powerful Framework for Change

“Nothing can make injustice just but mercy.”

— Robert Frost

Rather than a way to win a battle, mercy is a voice of reason that speaks for everyone involved. The persuasion of mercy is fair because it includes all perspectives. Beyond legal protocol, debate systems, prison, or physical punishment, as criminal justice attorney Bryan Stevenson points out, mercy is the answer to injustice. Mercy helps us find equitable solutions that are “just” by solving the problems without punishment. Merciful actions, such as restorative justice, are often surprising, usually healing, and sometimes apparently miraculous.

The concept of mercy is on a cultural rise, with Google Trends citing a steady increase in interest, and with popularity spikes related to films and stories with mercy in their titles. As we collectively reintroduce this term into public discourse, this section seeks to answer what mercy means in present times. While novelists, activists, and spiritual guides express their own interpretations, here we focus on practical skills to bring about mercy as compassion in action.

We believe that mercy is not just a practical virtue for ourselves and for community building, but is our most powerful weapon for peace and justice.

Our section is divided into three parts:

- Part I: Welcome Mercy defines the term, describes its roots, purpose, and shows how to welcome the three key virtues: understanding, forgiveness, and accountability.

- Part II: Expand Capacities suggests mind, body, and behavioral practices to expand the three key virtues into our homes and communities.

- Part III: Merciful Communication Methods introduces ways to communicate that tend to provide a merciful process for ourselves, and for others in a wide variety of group and community settings.

Part I: Welcome Mercy

Benefits of Welcoming Mercy

This part of our section is designed to help the reader internalize the virtues of mercy and create habits at home which can then carry mercy out into the community. Merciful practice helps build a foundation to:

- Experience greater compassion and other virtues in our lives

- Speak with authenticity and garner respect

- Build trust; form and solidify relationships

- Reduce conflict by offering alternatives to violent behavior

- Recognize and take responsibility for our own mistakes

- Forgive ourselves and others for doing harm

- Honor human needs respecting different boundaries

- Facilitate understanding and meaningful connections

- Create environments where mistakes can lead to reconciliation

- Empower others with practical tools to share mercy

- Confirm responsibilities for accountable next steps

The Roots of Mercy

“Taoism and Confucianism in China, monotheism in Israel, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism in India, and Greek rationalism in Europe—began with a recoil from violence, with looking into the heart to find the sources of violence in the human psyche.”

Throughout human history, religion has conveyed a sense of mercy, and congregational generosity has met many human needs. Though religions have justified merciless conduct, nowhere else but in scriptural writings do we find the ideals of mercy so explicitly discussed. Mercy is embedded in all faiths; even when God may be frightening, mercy is still portrayed as divine relief. Yet the call to do good for others is a common human bond, and mercy is the core of a healthy civil society.

Common Definition

The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary calls mercy “a kind or forgiving attitude towards somebody that you have the power to harm or right to punish.” Mercy is “a blessing that is an act of divine favor or compassion.”

The Purpose of Mercy

Mercy is an action that heals and prevents pain, especially appropriate when coming to the rescue of someone in need of relief and reliant on others for it. Mercy is absent in the all-too-common tragedy when those capable of easing pain choose instead to respond with negligence or violence. This is when, in community, those who are able to respond with mercy may resolve problems inherited from those who had failed to act with compassion.

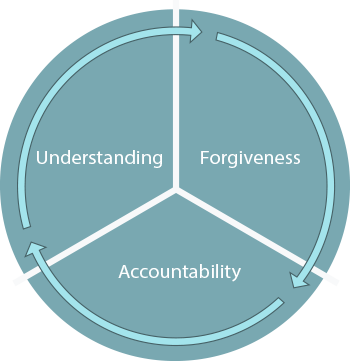

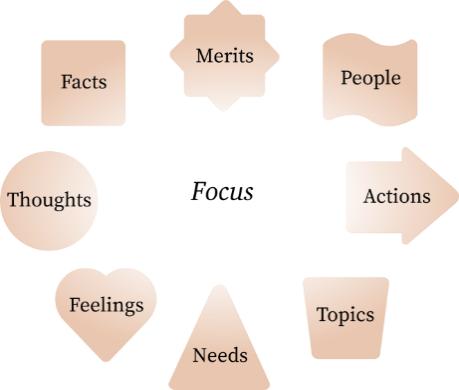

The Three Virtues of Mercy

There is no prescription to guarantee a merciful outcome, and often there is no logic or reason for its appearance. Mercy may come without bidding, and progress without any recognized process. But when wrongdoing persists, we may increase our chances of merciful results by taking action based upon three fundamental virtues:

- Understanding

- Forgiveness

- Accountability

Understanding is the grist for justice, forgiveness is the love for people, and accountability is the substance of reconciliation. With head, heart, and hands aligned for doing good, mercy integrates these virtues and gives us the momentum to move from wrong to right, and let justice unfold peacefully.

Mercy is compassion in action.

1. Welcome Understanding

“The noblest pleasure is the joy of understanding.”

— Leonardo da Vinci

Understanding is often the first step toward righting wrongs. Merciful understanding includes all relevant perspectives. Understanding others, however, does not mean agreement, condoning behavior, nor neglecting harm done.

Conflicts thrive on confusion of facts, motives, and judgments. Merciful techniques unravel this distress by welcoming contradictory facts, conclusions, and uncomfortable feelings within the umbrella of inclusivity. The wisdom of integrating seemingly incongruent information is consistent with Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory, which reconciles the common but confusing observation that people see reality differently.

Each of us is at different stages and levels of development. No matter our differences, when we confront basic human needs – from a position of equal influence as to outcomes – we usually agree on commonalities. Non-hierarchical inclusive leadership is one of the messages of Mirabai Starr’s “Wild Mercy.” Pulling from disparate faiths, Starr reassures her readers that everybody has something to bring to the table. There is a recognition that not only are we all connected, but that ambiguity and unpredictable contradictions are replacing “black-and white answers and fill-in-the blanks with these, [your own], beliefs.”

Misunderstanding, whether from ignorance or intellectual dishonesty, is dangerous and self-perpetuating. The playwright Tennessee Williams wrote that “hate is a feeling that can only exist where there is no understanding.” When information results in hatred, then it is likely that other perspectives are not represented, or represented incompletely.

Understanding that forwards the desires of only one group challenges the rest of us to think again. Emma Goldman, the famous utopian social activist, blamed the cruelty of ignorance, which “misunderstands always, condemns always.” People blame those who are victims of desperation for their crimes without understanding the causes of despair. A healthy economic and social environment, Goldman wrote, and “above all, a deep understanding for the needs of the child… would destroy the cruel, unjust, and criminal stigma imposed on the innocent young” who are born into poverty.

The processes of sifting through contradictions and human failings may be time-consuming and difficult, yet are likely critical steps in the unfolding of mercy. The dawning of knowledge itself is powerful and joyful. Understanding is a rewarding virtue which is often the first step in righting wrongs.

2. Welcome Forgiveness

When a wrong has been committed, forgiveness is often the central process motivating merciful action. Whether experienced as internal emotional shifts, or as part of legal and reconciliation proceedings, forgiveness unravels intangible entanglements that tend to perpetuate conflict. As with understanding, forgiveness does not mean agreement with or condoning inappropriate behavior, nor neglecting whatever harm had been done. Forgiveness is the conviction that the injury is behind us, no longer continuing or recurring. A merciful process seeks to resolve the wrong for those who suffered injury and also to heal, if able, those who caused injury.

Forgiveness is natural, usually automatic, process that we all experience on a regular basis, simply because life is full of human errors. Hannah Arendt wrote that without forgiveness we would be continually paying off each old mistake, and we would “remain victims of its consequences forever, like ‘the sorcerer's apprentice’ who lacked the magic formula to break the spell.”

Forgiveness can feel like heavy lifting, as both forgivers and forgiven give up whatever comfort we had gained to let go of self-righteousness. But once we change our attitudes, our receptivity changes; we have room for softening, and for letting feelings come through.

3. Welcome Accountability

“Accountability is the glue that bonds commitment to results.”

— Will Craig, Living the Hero’s Journey

Accountability is the action step that brings mercy to life. Whether in law, religion, fairy tales, or when begging, mercy goes beyond an inner sense of virtue to be the outward expression of our virtuous selves. Mirabai Starr notes that, while compassion “carries a quality of equanimity,” mercy “carries the quality of aliveness” that lights compassion on fire.

Though they are helpful, compassionate understanding and warm feelings are neither always necessary nor sufficient for a merciful deed to be done. It is rather the merit of the deed done, and not the sense of feelings of love, compassion, or righteousness, that validates an action as merciful. Intentional generosity on behalf of a person suffering isn’t mercy if it doesn’t relieve suffering. Beyond its precision, merciful behavior typically serves the needs of the moment in a way that takes into account what is seemingly good for everybody.

While personal feelings of understanding and forgiveness are often the spark for mercy, the “melting action of mercy” arises with action. It is compassionate action that distinguishes mercy as a virtue beyond compassionate thoughts or words that don’t respond to real needs being met. Sometimes words, acknowledgements of suffering, and sincere apologies are enough to resolve ill will; and in community restorative justice situations, mercy looks like the raising of people from their knees as criminals and outcasts to their feet as community members. Such truth and reconciliation may also bring relief from national and international suffering. The difference that mercy brings is our own human natural kindly way of behaving that is, at least our potential, if not our calling.

The Spiral of Mercy

The three virtues of mercy, especially as we expand our practices, potentially include more people and more complex issues, reflecting an upward spiral of merciful outcomes.

The Upward Spiral of Mercy

Part II: Expand Capacities

Having introduced the concept of mercy, with its qualities and benefits, we now take a look both at ourselves and others, in order to expand our awareness into greater capacities for mercy in our personal and community lives. Some of us think our own emotional shells are invisible, or impenetrable, or that all this “sentimentality” is irrelevant to real life. Yet mercy may emerge even when hearts are initially closed to tenderness and care.

Mercy Is a Human Virtue, Available to All

“Our prime purpose in life is to help others.”

— The Dalai Lama

Mercy is a natural human attribute, despite its rare acknowledgment. Humans commonly act empathically, from information garnered largely without verbal communication. We are literally wired to recognize the inner life of another person. For example, Dr. Giacomo Rizzolatti discovered “mirror neurons” in the human cortex which become active when we see someone else perform a physical action – as though it were our own motor nerves. Hatred, Rizzolatti believed, is learned behavior that holds us back from being habitually kind.

Dr. David Hamilton summarizes more recent evidence that human beings are wired for kindness because our compassionate acts have practical benefits. Kind actions protect against heart attacks and strokes, boost the immune system, and increase the duration of marriages.

Central to all major world religions and secular moral codes across cultures, mercy is universal. For those pursuing a virtuous life, mercy is the human choice for meeting needs. Though mercy is a core teaching of major world religions, religion is not necessary for mercy to flow. How we find a place for acting with honor, despite overwhelming emotions and life transitions, is personal. Though intertwined with religions, mercy is not beholden to any one in particular. It is action that reveals understanding and forgiveness, ever deepening as accountability unfolds.

Mary Johnson adopted Oshea Israel as her “spiritual son” – a young man who had, when he was 16 years old, murdered Mary’s only biologic son, then only 20. Mary thanks her Christian faith, and a poem about the commonality of pain, for urging her to reach out to Oshea in prison, in hopes of connection. Oshea attributes his response to her as the result of an internal process, “I was in a better place to hold myself accountable.”

Mary Johnson adopted Oshea Israel as her “spiritual son” – a young man who had, when he was 16 years old, murdered Mary’s only biologic son, then only 20. Mary thanks her Christian faith, and a poem about the commonality of pain, for urging her to reach out to Oshea in prison, in hopes of connection. Oshea attributes his response to her as the result of an internal process, “I was in a better place to hold myself accountable.”

Rukiye Abdul, in another court of law, after hearing two young men plead guilty to being the killers of her son, she stood up. Hugging the two teenagers, she said, “I don’t hate you. I can’t hate you. It’s not our way. Showing rahmah, mercy, that is our way.”

Rukiye Abdul, in another court of law, after hearing two young men plead guilty to being the killers of her son, she stood up. Hugging the two teenagers, she said, “I don’t hate you. I can’t hate you. It’s not our way. Showing rahmah, mercy, that is our way.”

This demonstration of Muslim behavior could also be called Christian. Examples of diverse peoples acting nobly underscore the universality of our human capacity for merciful behavior.

Expand Our Capacity to Understand

In any condition that mercy would rectify, whether in need or able to help, mutual understanding arrives by eliciting the comfort needed for anyone to share their truths or receive information with equanimity. The key mental states to engender understanding are listed here, all of which are enhanced by “mindfulness” practices such as meditation or contemplation. By regularly anchoring the calm and goodwill of a chosen practice discipline, our mind expands its capacity for understanding. An open mind hears and accepts feedback.

Most Important: Listen Carefully

Listening well uses all senses. To do so, empty our heads, smooth our brows, and lean in slightly with uncrossed limbs and full attention. Nonviolent communication and all of the protocols shown in Part III can guide our steps, but will fail to lead us to mercy unless we ourselves are prepared to offer the comfort of understanding. We relay understanding mostly by wordless recognition of the other as deserving of respect, with a posture and attitude of caring to hear what they mean to express. Listen for voices which cannot, for whatever reason, be heard, starting with those in the room, then in community and elsewhere.

Quiet Our Minds

Mindfulness practices, originating from many cultures and religious traditions, are popular and powerful for the cultivation of compassion, which warms our desire to act with mercy. Mindfulness helps us focus on the present moment and reduces self-judgment and reactivity. Regular mindfulness practice increases our sense of concern for others, our ability to handle stress, and helps us think more clearly. Such clarity helps us perceive needs that appear as “off-putting” behavior of others, and design creative ways to solve problems.

See with Listening Eyes

“One sees rightly only with the heart, the essential is invisible to the eyes.”

— Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Broaden our sights to include others’ perspectives by releasing the hold our own thoughts have on us, readying us for new information. Rather than asking questions about others, let people speak for themselves and notice their expressions and gestures as they bring new understanding of the human condition which is unique to each life.

Attend to Nonverbal Communication

What constitutes a respectful speaking distance, how we meet gazes, postures we strike, and gestures we use all have some cultural variability; however the following behaviors tend to communicate open listening:

- Relax body and mind.

- Balance and be still.

- Breathe calmly and slowly.

- Face one another with uncrossed limbs.

- Turn our eyes slightly down at times.

- Tilt an ear forward.

- Check eye contact occasionally, especially at poignant moments.

- Sense an interpersonal connection.

Question Our Conclusions

Thoughts set the defining direction for our actions, which then define us to each other – and to ourselves. Evaluating our thoughts before acting is the key to personal growth. It is sometimes helpful to consider the kind of thought we are thinking, and how its message serves us and others.

Byron Katie developed a system for rational thinking that she calls, “The Work,” using four questions to open the possibility of freeing our minds from negativity:

- Is it true? (Yes or no. If no, move to # 3.)

- Can I absolutely know that it's true? (Yes or No.)

- How do I react? What happens when I believe that thought?

- Who would I be without the thought?

What Katie calls a “turn-around” is toggling among contrasting meanings of words and phrases to find alternative “truths. For example, “He doesn’t care about me” can turn around to become each of the following, all with some degree of influence:

- “He cares about me.”

- “We care about each other.”

- “I don’t care about him.”

- “We don’t care about each other.”

This simple substitution of one potential reality for another might elicit different thoughts that help us interrupt our habitual reactions. Ridiculous turnarounds, like the last two examples, help us see where we exaggerate.

Toggle Other Perspectives

Mental flexibility is the capacity to view things from different perspectives, which broadens the reach of comprehension. Diversity of thinking informs diversity of actions toward merciful outcomes. Whether our understanding derives from comprehending root issues, learning different facts, recognizing common needs, or even suddenly noticing the humanity of another person – any one attitudinal switch can change how we view an entire situation. The more people we consider, each with varied influences on their perspectives, the more we comprehend a situation to develop remedies.

Choose Words Carefully

We are each responsible for our messages, unspoken and spoken, to oneself and others, as words can set off emotional responses and are often the pivotal act to welcome or reject mercy. Below is a list of what to avoid when communicating with people – there are more powerful ways to get a point across. More specific communication methods are outlined in Part III.

Merciful behavior is creative, not prescriptive, so the list of behaviors to avoid is basic. By keeping within these bounds we maintain clarity to understand, forgive, and make plans with people. Don’t critique or blame people; there are more effective ways to meet needs.

- Don’t talk until others are ready to hear, so that you can hear and be heard.

- Don’t label people, to avoid insulting them. Don’t tell people what to think, how they should be or what to do, in order to avoid trespassing boundaries.

- Don’t assume that we know what’s right and that other people are wrong, so that we can all keep our minds open.

- Don’t call people names or lump them in categories when describing what you experience; that makes it easier to understand, forgive, and resolve if there is a problem.

Take Responsibility for Our Responses

As listeners, we are likewise responsible for our responses to words we hear, regardless of our histories and emotions. Even when the intention to hurt seems clear, a merciful attitude considers that the rationale may be understandable, the person responsible for harm forgivable, and the situation remediable.

Focus on Authenticity

Simply repeating a speaker’s own wording may not reflect compassion or understanding. Instead:

- Encourage people to share their reasoning.

- Consider what it might be like to be in their shoes.

- Float responses gingerly to test people’s reactions.

- Confirm that our understanding rings true for them.

- Respond authentically and transparently to maintain mutual trust.

- Speak for all who may be hurt in the given matter.

- Convey a desire to conclude with understanding and trust.

- Close with subtopics concluded or continued accountably.

Let People Speak Freely

Though we recommend using clear structures to ease complex conversation, methods themselves can sometimes be a form of silencing. Groups can agree to rules, such as no cursing, no violent gestures, or no raised voices; however, when individuals in great distress “act out” – that is, display their despair – merciful systems provide an ally to be with the person in pain. Rather than shut people down, we can recruit members within the same communities to help them reframe expressions. Community workers and allies can track subtopics with accountability and return to them when there is time for attention to the feelings, needs, and full meanings of the expression.

Encourage people to explain from personal experiences so that we experience changing positions. Community workers can create safety for conversations by ensuring that opposing views are respectfully heard and understood, and that values, needs, and feelings are shared.

Expand Our Scope of Understanding

As understanding resolves needless misunderstandings in countless households daily, mutual understanding could resolve today’s problems of global significance. Merciful solutions are inclusive of all people involved, and invite all people to the table with mutual respect. Only when all relevant influences are understood can valid conclusions be drawn and actions decided.

Bring Understanding to the Internet

The Internet has held promise of bringing people together, but current social media actually encourages conflict. Community workers inspired to act with compassion increasingly speak, text, chat, and blog with merciful outcomes in mind. We supplement face-to-face meetings with online communicating to keep interested people informed and involved. We supplement online communication with human kindness face to face.

With online interaction infused with bots, let alone the percentage of malicious bots, as well as uncited, unvetted fake news, the role of human mercy on the Internet is confused due to lack of accountability and unexamined emotional responses and bot triggers. Robots don’t have human needs, so they don’t sense the responsibility inherent in mercy – they aren’t bothered by human suffering. The responsibility rests upon us humans to sway the future toward merciful outcomes.

Expand Our Capacity to Forgive

“Dare to connect with your heart. You will be lifting not only yourself and those you love and care about, but also the world in which you live.”

— Doc Childre, HeartMath Founder

While understanding is predominantly a mental exercise, forgiveness is mostly an emotional experience. Mindfulness exercises, described above, gain power when grounded in the body. A hand on heart or belly when breathing deeply can anchor a calm mind. Whether we talk ourselves into thinking about things differently, or physically release our feelings in order to no longer feel overwhelmed, either action changes the other. To resolve the spiral, we continue to process pain until we have a working plan that serves everyone involved.

Practice Being Present with Our Feelings

“If there is a single definition of healing it is to enter with mercy and awareness those pains, mental and physical, from which we have withdrawn in judgment and dismay.”

— Stephen Levine, A Year to Live: How to Live This Year as if It Were Your Last

Most of our habitual reactions to life’s challenges were formed when we were very young, and are often hidden from our notice. The very patterns we don’t see in our own behavior can annoy us when coming from others; they are like uninvited visitors who act out without asking our permission, or even making any sense. These tendencies happen automatically until we pay attention to defensive patterns that work in the background. This takes insight, and willingness to feel and emote. Forgiving ourselves for patterns we’ve had trouble controlling helps us forgive other people for their hurtful patterns, which they don’t see either!

Allow Emotionality without Judgment

The greatest challenges on the road from conflict to peace and good will are often caused by resistance to personal emotional discomfort, coupled with incriminating thoughts. This is the moment to call upon the gift of our practiced mental and/or physical discipline. Remember the anchor we’ve practiced to encourage our virtuous selves to rise above old thought patterns and enliven positive feelings. This willingness to feel emotions with an open mind initiates a merciful process that can transform agony to relief, from the inside out. These are the moments in which we practice opening our gates to mercy.

Simply by recalling a mindful presence, we create a subtle separateness from conditioned reflexes, and gain an opportunity to experience emotional distress with fluidity in our mental and physical selves. By shining a light on our usual reasoning, we allow new ideas to appear that cushion the process of emotion.

Feeling Is Not Rational

Relinquish the habitual urge to analyze our turbulent internal weather. Imagine letting go of a kite string that is pulling away a storm cloud of old assumptions and bitterness. Our minds and bodies become as a wordless witness to our breathing, as feelings such as grief, fear, shame, and disgust wash through and clean us. The process of releasing habits of mind while withstanding unpleasant sensations takes its own time, and tends to cycle with increasing clarity as each tempest passes.

Start Where You Are

“Start Where You Are” is an invitation to meditation coined by Pema Chodron to awaken the compassionate heart by welcoming the very pain we’d rather deny or suppress. She states, “Forgiveness begins for victims when we embrace the pain and loss. We go straight into those rotting places of shame, guilt, anger, and fear, and question the thoughts that threaten healthy self-identity.” Emotional releases clear the mind like rainstorms clear the air. As Michael A. Singer puts it in The Untethered Soul, “When you are comfortable with pain passing through you, you will be free.”

Accept Our Unwanted Parts

“Each of us is more than the worst thing we've ever done.”

Alan Watts, speaking of the greatest lessons learned from Carl Jung, said that no matter how righteous we may appear to ourselves and in society, each of us has the potential for unmerciful, even cruel, actions. Yet the shadow self is “not as something to be condemned and wailed over but as something to be recognized as contributive to one's greatness and to one's positive aspects in the same way that manure is contributive to the perfume of the rose.” The more we accept our own potential to do harm, the more we expand the capacity to accept harm done and forgive ourselves and others.

Accept Others’ Unwanted Parts

The understanding aspect of mercy includes viewing the issue at hand from all angles. The release of whatever attitude restricts us from recognizing the humanity of someone else is typically an emotional experience. The outcome of considering even unpleasant realities with compassion broadens potentials of new thoughts, feelings, and actions.

For example, when we imagine a wrongdoer being tender to a child or elder, as when a family member demonstrates yet another of many parts, we realize that there is more there than meets the eye. Even when our hearts are infused with rage, when we conjure a sense of humanity for others who have hurt us, we feel the “melting of mercy” that Starr emphasizes. As our realizations affect our feelings, intentionally eliciting a warm feeling can help us realize that harmful deeds are by nature forgivable.

Forgive While Sitting, Walking, Dancing, Praying with Pain

In the moment, breathe slowly and deeply to bring self-healing. Consider something beautiful – real or imaginary, flowing or still. Wrap any uncomfortable sensation in light, sound, energy, prayer, chant, or other sensation of merciful expression. Music, visual art, and dance reflect the tempos and intensities of our feelings and mediate release of painful emotions. Write dreams, poetry, songs, list what we are grateful for; dance, shake, weep freely if so moved.

Discharge Emotion

Harvey Jackins happened upon what later became known as “Co-Counseling” in the process of helping a friend of a friend get over immobilizing depression after World War Two. He and other friends began helping each other release emotional pain and developed a distributed model of self-help, in pairs and groups, called Co-Counseling, or “Re-Evaluation Counseling.” They found that emotional discharge, when allowed a full cycle, has a typical pattern, from grief though fear and anger to boredom and then zest.

Music, video and other forms of art – especially those in which we participate, can mediate emotional expression. Bodywork and reflective movement forms such as yoga can release tension without overt emotional expression. Specific movements and physical exercises are also helpful to open the body to emotional release. Alexander Lowen demonstrated these tools in his 1976 landmark self-help book, Bioenergetics: The Revolutionary Therapy That Uses the Language of the Body to Heal the Problems of the Mind.

The Grounding Posture in Bioenergetics

The Grounding Posture in Bioenergetics

Accordingly, follow emotional releases with “up and out” activities to bring our attention to the present moment: Center in a grounding pose, drink water, walk in nature, play with an animal, talk to a friend, get some exercise, eat carefully, and then take time to serve the needs of someone else.

Cultivate Forgiveness

Take time to feel each of the numbered sentences following under this heading, and let faces and memories wash through the body. Conceive of issues as clouds blowing away or detritus floating down stream.

Ho’oponopono

Ho’oponopono is a Hawaiian phrase that means to “set right what was wrong”; it is a synonym for mercy. The term often refers to the following four-line prayer/poem, but this Hawaiian tradition of healing and peacemaking is practiced in many forms world-wide. It is a concept, method, technique, and way of life that promotes a culture of peace and nonviolence, including counseling, addiction recovery, social activism, and restorative justice practices.

The following Hawaiian phrase was popularized by Dr. Ihaleakala Hew Len, to help process difficult memories and related emotions that may no longer serve us. As we repeat the phrase, we gain understanding as words bring up images from our past, such as faces and events. Emotions flow during the exercise as we adopt responsibility for whatever we experience in ourselves and others, which is cleansing for any parts of our lives, and can be healing to others` lives too.

"I’m sorry, please forgive me, thank you, I love you."

Practice Forgiveness in All Directions

One variation of a forgiveness exercise seeks to cleanse potential issues from all “directions”; from self to others, others to self, self to self and others all, and each to oneself.

- “I forgive myself for harming myself.”

- “I forgive myself for harming you.”

- “I forgive you for harming yourself.”

- “I forgive you for harming me.”

- “I forgive us all for harming each other.”

We Learn Forgiveness through Pain

Miribai Starr, the author of Wild Mercy, describes the experience of her own daughter’s early death. She noticed, in the throes of her own anguish, “We open and close like an accordion, in the power, the bellows of loss.” It is through the experience of life’s pain that we expand the capacity to soften and open up the hard spots so that forgiveness can flow, and thoughts can shift into action.

Enjoy Release from Pain

Once we learn how to be still with ever more difficult feelings, we anchor our sensibility to weather times of great distress and pain. This practice helps others, too, because people can sense and be comforted by our calm. Once we are not confused, angry, or fearful we can think clearly and understand our situation from different perspectives. Our hearts are softened; we can forgive. We can speak of our needs and boundaries, respect those of others, and figure out what to do next.

Process Again

Emotional processes tend to cycle a few times before release, as layers of feeling are peeled away. Olga Botcharova suggests that we name each of our fears one by one, drawing it into the light for examination. When we are hurt, “We are usually more fearful of the emotions that accompany our fears than of the fears themselves. Through time and courage, what were fatal tragedies become challenges overcome. We reap the benefit of clear thinking and peace about our lives.”

After injury, the realization of loss and its associated panic leads us to a critical decision point: We either feel and express our grief or try to suppress it. When we don’t process the pain, we tend to fall into cycles of asking “Why me?,” and imagining revenge. If this continues, we can fall into imagining “justified” aggression. This then creates further pain, for us to process and resolve.

Be Merciful with Emotions

A merciful approach to emotion lets us express our pain, name our fears, and open our hearts to questions like “Why them?,” which re-humanizes the enemy. From this point, it is far easier to recognize the ease of forgiveness, because we are not blinded by suppressed pain requesting attention. We can nourish a space for both the wrong-doer and the one injured by the deed, when both are seen as fully human. Justice can then take form as people collaborate on a shared future in light of mutual accountability.

Take Cues from Signs of Discomfort

As we become friendlier with our own internal sensations, we become more attuned to, and comfortable with, what other people may be experiencing. Seek out those who need an open heart to listen, and practice compassion – whether that someone is sitting across from the dinner table, riding next to us on a bus, or living deep in a lonely prison. Tuning into others also means attending to nonverbal messages from others throughout the day. Notice when people:

- Change volume or speed of speech

- Shift positions, sink back, or get up to leave or pace

- Bite lips, raise eyebrows, look away, look around or stare

- Take sharp in-breaths, or hold their breath

- Start tapping a finger or foot, or wringing hands

- Cross arms or legs.

These behaviors indicate discomfort that can inform our own responses. When we see agitation arise, we can consciously calm ourselves and call upon merciful tones of voice and choose empathic words. We may offer some comfort, such as, “Is there something you would like to say at this point?,” or, “Would you like to choose an ally to help get your point across?”

Expand Our Scope of Forgiveness

Forgiveness begins as an internal process, and usually bears fruit as it ripens into merciful action. It is important to let communication come to full fruition, especially word-free resonance with another’s experience. People may come forward to speak their minds later, and want to continue subtopics that were postponed, or add new ones. It’s important as well to set up ongoing systems of communication, so that people have a trusted place to “park” concerns that are set aside to process the initial focus. People who could not attend or want to be included in the conversation will bring in larger communities.

Find Each Other for Support

We need each other to access, accept, and transform some hidden pains to clear away unconsciously-driven feelings and reactions. See Part III for Co-Counseling and other resources for mutual support. Introduce family, friends, co-workers, and neighbors to these concepts and methods so that you can better help each other recognize and get through the rough patches.

Stand Ready for Mercy

Our bodies reflect and inform our mental states: We can practice the feeling sense of forgiveness through our own physical presence. We feed back to ourselves and others a softness in relaxed stance and movements. We feel and convey caring with a gentle head-tilt, listening with continuous attention, with intermittent approving gazes. These actions are natural and automatic once we have found compassion, as is an open posture that shows an expectation of mercy that is about to unfold.

With conscious attention to our bodies’ reactions, we orchestrate our otherwise unconscious behaviors. Our breathing, facial expressions, and body posture affect our own sense of how we feel and how open to forgiveness we are; they also emit peaceful “vibes,” to inform others of the potential presence of mercy.

Expand Our Capacity For Accountability

Our daily lives provide the material for practicing the integrity of keeping our word, and making good on our commitments to ourselves and others, including the responsibility we take for our interpersonal behavior, especially when we are in the wrong. Just as when we are injured, we practice applying the balm of forgiveness, so when we trespass on others we practice voicing options to repair damages.

Surprisingly often, people are satisfied with receiving recognition of our pain, and an apology is all that is required to heal a wound and put it in our past. Nonetheless, it is merciful to not just share our regrets but also to offer make whole those who are injured, as well as prevent a similar situation from arising in the future. When restitution is in order, we act to make up time, restore property, or help in some other way.

Account for Our Own Mercy

In the study of mercy, our first subject is our own behavior. Start where we are in our daily lives in relation with our families and friends. Try asking yourself.

Am I Merciful?

- Do I understand and forgive myself and others?

- Do I honor key virtues in myself and others?

- Do I act upon urges to help others?

- Do my deeds bring healthy results for others?

- Do I enjoy the fruits of mercy for myself and others

Take Personal Responsibility as Able

Understanding and forgiveness may offer a set of potential actions, but do not predetermine a specific action, as does a typical criminal justice system. Whether or not we have had a hand in the cause of pain, people who are witnesses and members of community are also affected and can contribute to an accountable process. Bryan Stevenson, social justice attorney, notes that “Simply punishing the broken—walking away from them or hiding them from sight—only ensures that they remain broken and we do, too. There is no wholeness outside of our reciprocal humanity.” We are each responsible for our own actions as an individual, a member of our clan, a worker in community, and, as we can, an active member of our generation.

Merciful action in community blossoms when individuals take responsibility, together, for the effects of our behavior for ourselves and future generations. The potential for individual responsibility in merciful processes continues all the way through fulfillment stages, as accountability is measured by the problem at hand being resolved or resolving as a result of merciful actions. This process humanizes and connects people around wrongdoings to set things right, in ever greater spheres of influence, for ourselves, our people, and ever more people, as we expand our capacities to follow through with responsibilities with accountability.

Serve Others

Mercy for self and others are entwined, so we commonly reap the fruits of mercy for ourselves as we serve others, and vice versa. Ram Dass, author of Be Here Now, demonstrated how service to others is integral to life and love and to relieve our own suffering. Mercy for self is healing for others as well. “To be available for someone else’s suffering you have to be able to acknowledge your own suffering and be able to understand the nature of suffering in such a way that you have converted the quality of suffering in yourself.”

Notice Our Communication Habits

It’s easy to see antagonistic communication in others, but the power to change comes from recognizing these reactions in ourselves and being willing to stop them, even as they are occurring. The table below helps to clarify:

| Merciful Communication | Antagonistic Communication |

| Check in with people to see if it’s a good time for the topic. | Barge in with an urgent demand for attention. |

| Attend to others thoroughly; insert silence between points to reflect on what the other means to say, or how they feel. | Interrupt, rush, talk over other people; or think about a response before the other is finished. |

| Respect people as being greater than one or more actions they did or didn’t do. | Label or blame people rather than behaviors and circumstances. |

| Focus on the moment, except to clarify misunderstandings. | Bring up past offenses. |

| Uphold equanimity with calm and even tones. | Exaggerate, belittle, mock, fret, and talk a lot. |

Assess Results of Our Behavior

Unfortunately, our best intentions are often thwarted by unconscious emotional reactivity. Competitive actions tend to trigger more reactions, like a downward spiral, until someone acts to break the cycle. But compassionate actions tend to reverse the direction and help generate an upward spiral.

| Interpersonal Approaches and Their Likely Results | |

| Compassionate Actions | Competitive Actions |

| Understanding | Dismissal and Rejection |

| Forgiveness | Blame and Guilt |

| Resolution of Pain | Punishment and Suffering |

Remorse and promises of abstention often fail to inspire a person to avoid any “bad” habit, both because the habit is addictive and because somehow it helps avoid certain pain, even as it causes other problems and pains. The merciful solution is discovered through finding and resolving pain which otherwise continues to provoke the unwanted behavior.

Be Merciful with Behavior

It’s ideal to keep awareness going all the time to prevent hurtful behavior; but the sooner we realize we are being triggered after the fact, the sooner we can take a merciful approach. A simple “Let’s take a break for a few minutes and reconvene,” may be sufficient for people involved to take account of their behavior. A little distance in time and space helps us remember to be mindful and process emotions to discover more virtuous actions we can take.

Reset Our Approach

If anchoring our personal practice by itself falls short of restoring our urge to act with compassion, it can help to lean on the three steps of mercy, or other ethical lampposts. Merciful behavior echoes the ethical precepts which the Buddha taught that his monks, 2600 years ago, as a central process for growth in their discipline. Practically, this means recognizing and making amends for our transgressions and undertaking future restraint. We are always responsible for our conscious choices.

- Always put ourselves in the other person's place.

- All beings are worthy of respect.

- Regard those who point out our faults as if they were pointing out treasure.

- No higher purposes excuse breaking these basic precepts.

Catch Ourselves before the Act

Our first level of accountability is to what we most control – our own words and actions. Before accusing another of doing wrong, the Buddha recommends asking oneself:

- Am I free from unreconciled offenses of my own?

- Am I motivated by kindness, rather than vengeance?

- Am I clear about our mutual values?

Speak only if the answer is “yes” to all three questions.

Speak only what is true, timely, gentle, to the point, and prompted by kindness.

Move Beyond Feeling Sorry to Making Amends

Apologizing may be integral to a restorative process; however, mercy goes beyond feeling badly about oneself or simply admitting wrongdoing, to making things right all around. The heart of mercy yields to solutions that insofar as possible may restore all parties, heal all wounds, and respect all persons. Mercy includes an action to conclude a harmful process, with a reconciliation that is accountable.

Offer Accountability for Transgressions in Community

Merciful accountability, such as in restorative justice procedures, helps the one responsible for harming others make good on a mistake and offers a clear path for rejoining the community. Processes may involve family, community and institutional structures using accountable ledgers, to assure fair and just restitution.

Stand with Each Other as We Hold Each Other Accountable

Merciful spaces call upon us each to stand with each other when any one or more of us falters. Unlike punitive methods that neglect the needs of those injured, mercy lifts the potential of accountable reconciliation. Unlike punitive methods which dis-empower a wrongdoer from making good, merciful processes create structures within which we can come to terms with the effects of our errors. In punitive environments, humiliation holds us back from assuming ownership of our mistakes. But when fear of punishment is lifted, we tend to acknowledge our own misdeeds and disclose uncomfortable facts, feelings, and thoughts that would typically be withheld, or even be condemning.

Within the safety of mercy, we accept life’s painful lessons and actively transform pain into accountable plans. Again in contrast with punitive methods, with merciful systems we uphold the nobility of people who pronounce self-responsibility and deliver accountable reparations.

Tough Love

Tough love is about holding people accountable, not endorsing punishment. Ted Wachtel, who helped popularize the term, promotes restorative practices to repair interpersonal harm caused by crime. Teaching “you are bad” or “you must suffer,” is counterproductive to changing behavior. Tough love welcomes the deed doer to make good oneself. This paradigm has led to innovation and research integrating merciful practices into the criminal justice system, schools, therapy, work, and home settings.

Balance Responsibilities

Community workers, often caught between awareness of huge human needs and our own human limitations, may find balance in the practice of mercy. Personal boundaries for self-care are not just consistent with, but necessary for bringing mercy to others. Our dedication to service is nuanced with contradictions as we step in and out of seemingly contradictory roles in wildly different contexts, yet impossibly distinct parts of ourselves are all welcomed by merciful reflection.

Admired for extremely light living in the wilderness, Lynx Vilden, who forages for her meals in deerskin clothing she made herself, occasionally hops on an airplane. Vilden’s strenuous lifestyle leaves a tiny footprint that would be perilous for most of us. We each draw our own circles of personal responsibility and choose the measures by which we hold ourselves accountable.

Assess Our Accountability

Our latest generations are commonly faulted by prior generations for lack of responsibility in passing off problems which, for the first time in history, threaten survival of all we know. But not only do young people inherit wreckage they did not cause, those who have been responsible imply that we arrived here as a matter of inevitable chance. This compounds the psychological trauma of their already overwhelming inheritance by psychologically shutting down individual recognition of their own agency. Continued economic norms further disempower youth by teaching that the only way out is the entrepreneurial dream of striking it rich – to be accountable only to self. Mercy, on the other hand, suggests a broader understanding and depth of care as each of us flicker for our time on the planet.

To whom am I accountable and for what?

Who would I be if I were more accountable?

What would I give up to be more accountable now?

Expand Our Scope of Accountability

In a merciful space, we become aware of pain, our own and others’, here and across the globe. We also recognize cultural and intergenerational pain. The burden of unresolved trauma, passed from one generation to the next, as Gabor Maté explains, requires both individual and societal work to arrive at the compassion required to heal on these two levels.

According to the contemporary philosopher Ken Wilber, our personal and cultural maturity evolves through parallel, integral processes, as individuals and groups work through our stages and levels. It is us our responsibility to shift the trends toward a merciful paradigm, starting with ourselves. Tami Ritter, who brought restorative justice to the Chico, California community, personally shared this sentiment with the authors: “The idea of mercy is to be fully restorative. We are all flawed, wounded, and broken in some way. All parties need to be restored, so we extend mercy to ourselves as well – and we acknowledge that.”

Reversing the traps of both personal and cultural trauma-triggered behavior is a primary purpose for bringing mercy into the world. Ideally, face-to-face connections will be bolstered by efforts to bring kind communication to the Internet, to meet people where we can connect – online and offline – with tools that resolve unmet needs with the ongoing accountability of systems promoting real solutions.

Prevent Harm in the Future

Mercy is not simply a matter of leniency, nor a matter of “letting people off the hook.” It is not “turning a blind eye” to violent and hurtful behavior. It is the understanding that punishment is not, at least in the instance at hand, required for justice. The gift of mercy, when accepted by the wrong-doer, takes the place of punishment to re-create wholeness for all involved.

Practice Daily to Build Capacities

Beyond a wholesome discipline, be gentle with yourself.”

— Max Ehrmann

As a physician and a minister, we humbly acknowledge that mercy can arise spontaneously, as there is no “one-size-fits-all” for peace of mind. Most people seem to find merciful ways through recovery from various traumas. Many find a community of faith or ideology that is prepared to help people process life’s transitions. We find mercy in our own ways, and expand our capacities through disciplines such as meditation, yoga, breath work, contemplation, dance, art, music, insight, bodywork, martial arts, prayer, injury, healings, and friendship, not to mention methods we haven’t personally experienced.

We recommend that people choose disciplines to enjoy and practice on a regular basis, and judge them by an expanding sense of mercy in daily life. The more we hone our individual skills to recognize need and bring relief, the greater our power to cause mercy to regularly flow in our lives. We can practice mercy where we hold most influence: within ourselves, then among people at home, and then in work, social, and religious groups. In our experience, the more we practice, model and teach these habits, the greater capacity we have to bring about mercy for the larger good.

Discipline Gives Us Time to Pause and Reset

Mindful and somatic practices, with particular focus on understanding and engendering compassion, are those most likely to bear the fruits of mercy. As we feel better, we increase our personal capacities to do good for others. Our core practice provides an awareness of our inner reactivity. When we find ourselves indulging a nasty thought or unpleasant feeling, aching to swirl out of control, we have the skills to honor, heal, and resolve the underlying discomfort.

Give Time and Attention

When asked “What can we do?,” His Holiness the Dalai Lama often has recommended taking a walk with a neighbor. This seemingly trivial practice of human connection has powerful healing potential. There is no substitute for spending time and attention for the merciful resolution of human need.

Two vignettes illustrate this point:

Darryl Davis is a Black blues musician who connects with people around music. He is particularly good at reaching out to, and deeply changing, members of the white supremacist group, the Ku Klux Klan, or KKK. He respects their longing for belonging and offers them more merciful options for meeting these needs. His efforts have been effective. Klan members literally forsake their racist oaths and give up their robes – Davis has the world’s largest collection of KKK regalia.

Allison taught yoga to men in prisons who were sometimes three times her weight, with backgrounds so different from hers that a connection would have seemed unlikely. But her teachings, said her students, helped them maintain sanity under harsh physical and emotional conditions such as solitary confinement.

Practice Mercy Daily

Regular practice will build the skill and equanimity to act compassionately in the face of personal and community challenges.

- Start and end each day with a compassionate practice.

- Reflect upon, express, and reinforce kind actions.

- Notice where mercy is lacking, and apply compassion throughout the day.

- Let love and gratitude be touchstones for our words and deeds.

Anchor a Sense of Mercy

A daily practice offers us an anchor – maybe a position of the eyes, hands, or way of breathing – that helps us remember how it feels to be calm. Remember the three virtues of understanding, forgiveness, and accountability to become present, and have the wherewithal to pause and choose our reactions. Remembering this pause at home and among co-workers and friends will encourage a good habit that becomes easier with practice. We’ll know if the anchor is working when, even at the start, we notice that friction has resolved, decisions are more easily made, and people walk away from a situation feeling satisfied.

Practice Anchors of Mercy

We all have habits of behavior that “pop up,” triggered without our conscious choice. It’s common to spot reactivity in others; but the power to change comes from recognizing our own reactions and stopping them, even as they are occurring. As soon as we catch ourselves reacting in an unpleasant and usually habitual way, whether by raising our voice, walking away, blaming ourselves or someone else, faking emotions or making excuses – wake up now and remember our own anchor.

Whether a phrase, such as “mercy now”; a concept, such as understanding; a feeling, such as compassion; a movement, such as a way of breathing; or a posture, such as lengthening one’s spine, we can train ourselves to attend to a presence of mind and calmness of spirit to act from understanding and compassion.

Practice Mercy at Home and among Friends

Home practice is among the most challenging of venues for calling on mercy; yet it is basic training because of the precious feedback we get from family. Practicing merciful sensibilities at homes instills confidence that we can also bring mercy to our friends, co-workers, and into community.

Some thoughts on how to nourish a merciful home:

- Attend to oneself and others by listening.

- Bring relief to others when possible.

- Share meals, outings, and heartfelt conversations.

- Pitch in with daily chores.

- Speak with appreciation for each other.

- Laugh together.

Steps for Mercy with a Loved One

- Reassure with love and flexibility.

- Speak with a tender tone, free of criticism.

- Listen and validate what we hear.

- Make any issue "our problem," rather than somebody’s fault.

- Find agreement with welcome compromise.

Behaviors among family and our inner circles become healing when we give attention and time to each individual. We can listen for the tone in our voices. We can slow down to add grace to our movements, and consciously help each other navigate the logistics of day-to-day life.

Set Boundaries

Whether acting as individuals or in groups, we define behaviors that are and are not acceptable for ourselves and others. Mercy holds respect for similar and individualized boundaries; we may share the same needs, but not the strategies to fulfill them. Each one of us defines our own boundaries in different situations, and, with practice, our own ways to ensure that they are honored.

Respect Boundaries for Everyone

“As far as possible without surrender be on good terms with all persons.”

As we practice mercy with loved ones, we feel increasingly comfortable with setting boundaries – with our family members, friends, and communities.

Distinguish Threatening Words

To censor insulting words may feel like setting boundaries, but can be an alarming distraction from real harm being done. Rather than being insulted by words, we practice seeking the speaker’s emotion and underlying needs. Similarly, we can also understand and forgive people who themselves may be insulted by something we’ve said. When a spoken word, regardless of the intent of the speaker, incites anger, it is helpful for an ally to mediate the expression to mediate understanding and forgiveness. When language is threatening, we use minimal force to prevent action that exposes anyone to harm or physical and emotional insult.

Keep Boundaries Kind

When utterances of one person cross comfort lines of someone else, the methods described in Part III, to follow, are handy to reveal and process the underlying transgressions to quickly find a remedy. These structures create boundaries that help us avoid misunderstanding and insulting each other. They also help us take the time and attention for human needs. Remember, communication methods alone can turn into failed communication traps unless understanding is prioritized, compassion is sincerely felt, and actions truly reduce suffering.

Expand Our Scope of Merciful Practice

The skills of setting physical and emotional balance assist in the creation of merciful outcomes. Effective communication is typically the first action to take to evoke mercy in various situations. Efficacy of mercy depends primarily on the trust that is built on safe, transparent verbal expression and a shared goal of mutual satisfaction with the likelihood of needs being met.

Practice Kind and Effective Communication

- Take turns.

- Be curious and attentive to the speaker.

- Listen for main points and underlying messages.

- Allow time for emotions to catch up with new thoughts.

- Be aware of nonverbal communications.

- Give the same consideration to everyone, including ourselves.

- Honor any form of emotional response as a clue to valid pain.

- Tailor understanding, forgiveness, and amends to each situation.

- Conclude with an accountable plan that satisfies all involved.

Set the Stage for Mercy in Community

Community workers can set the stage to encourage merciful outcomes whenever people gather around an issue. Consider everyone’s needs, and choose methods appropriate to the situation. Some key aspects of setting the stage for mercy in community are outlined below:

- Safety is a basic need that those working in community are responsible to protect, both physically and emotionally, at least in terms of preventing harm. From a merciful perspective, emotional safety allows for relaxation, mutual connections, and a cushion of support assuring that care for our basic needs is, and will remain, in focus. Security personnel may be trained in nonviolent tactics and careful communication methods. Mercy, complete with a plan to do something tangible to heal or prevent injury, is an outcome of physical and emotional safety.

- Respect is the currency for merciful interactions. Each of us can mint our own respect by balancing humility with self-care, and so have plenty of capacity to dispense equal shares of regard for wrong-doers as we do for those injured. Stand up with those caught in shameful acts as we do for those abused. Include the entire community among those who “count” in merciful processes.

- Comfort is a primary goal in setting the stage for mercy. As facilitators are able, prepare emotional and physical surroundings for comfortable sound, lighting, and temperature. Welcome everyone with warm and open presence, and show them options for seating, viewing materials, and meeting people. Provide snacks, and note bathroom facilities. Match ice-breakers and music to the reason for convening. Be sure that housekeeping needs are identified and promptly handled.

- Inclusion is at the heart of mercy. Be sure that outreach has been broad, in that community members from all ideologies, colors, origins, and opinions are welcome. Honor the dignity of each member of what Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King called “our beloved community.” Keep group processes and roles transparent with an “all together now” momentum that has nothing to hide. Openly and critically discuss protocols to carry out strategies of action, and review potential effects on all parties. Merciful processes also extend through and beyond the conclusion of meeting needs. Give support to a variety of causes, even if they may not dovetail completely with our own.

- Expression is the voice of mercy. When we come together, let us talk, meet, and mingle. At the minimum, two minutes of sharing, most efficiently in pairs, is a wise investment, as members of the group transition to being present with each other. Chanting, clapping, singing, physical movement, humor, mingling, and worship meet various individual needs and consolidate the group. When open and expressive communication occurs, the comfort that results helps create a welcoming environment for mercy to appear.

- Support for human needs is the essence of mercy. Beyond concerns for safety, group process, and time considerations for arriving at a workable conclusion, merciful facilitation promotes connection and mutual success with inclusion of all who may be involved. Such facilitation includes:

- Supporting participant needs for protection, convenience, wheelchair access, transportation, and child or elder care.

- Having signers and translators available.

- Attracting facilitators who are trained to handle individualized needs of community members and are genuinely present for all people.

- Setting up systems for all kinds of connections, with various community members taking co-responsibility for loose ends until the conclusion of a get-together.

- Establishing communication around events and issues that people care about to keep the momentum going with adequate support.

Share Responsibility with Accountability

Community workers model responsible behavior by being accountable to agreements, with responsibility for our own tasks and behaviors, including making amends for mistakes. We also encourage others to come together around shared problems, by demonstrating our own sense of shared responsibility. When we recognize injustice, we call upon the community to join together to resolve problems with justice and dignity.

Responsibility in merciful processes continues accountably until the problem at hand is resolved or resolving and needs are met for all as relevant. On a personal level, mercy is the understanding, forgiveness, and accountability that resolves individual and family or group pain. The process humanizes and connects people around wrongdoing to make it right, in ever greater spheres of influence – for ourselves, our people, and ever more people, as we expand our capacities. Merciful action in expanded communities blossoms when individuals take responsibility, together, for the effects of our behavior on future generations.

Respond to Violence with Mercy

Marshall Rosenberg, who developed a pivotal communication method, Nonviolent Communication (NVC), described below and in Part III, often said that tense and even harmful behaviors are “tragic expressions of unmet needs.” A merciful response when someone is threatening or attempting violence is a strategic decision to avoid accelerating violence. If you are a position to do so, train security personnel with nonviolent communication tools and gentle methods of physical restraint. Also when able, in the face of threat:

- Keep an arm’s length distance.

- Turn a bit to the side, to avoid appearing to “face-off.”

- Communicate clear goals in a way that is likely to seem fair and reasonable.

- Be attentive, without glaring.

- Move slowly, making no abrupt gestures.

- Speak gently.

- Say what you are going to do before doing it.

- Don't argue, or say anything critical or threatening.

- Uphold boundaries without blame; don’t say, for example, “This is disrupting the meeting” or “We don’t shout in here.”

- Try a variety of tactics; do something unexpected and creative to change the mood.

- Reassure the person who is engaging in destructive behavior that we want to understand their perspective and meet their needs.

- Become or recruit an ally to offer to support the person’s needs being met.

- Encourage the person to express themselves, following the methods below to show understanding.

Make Amends with Mercy

While forgiveness alone may calm our responses, merciful processes resolve past harm and set up structures for mutual safety in future interactions. Mercy for harm done unfolds uniquely in each situation, with some basic commonalities.

The first step is to recognize a harm, or even a verbal insensitivity in another – at home, in the workplace, or in community. Reframe the situation to meet the needs of all involved by putting basic human needs first. Follow a logical process to review all facts, assumptions, and beliefs from different perspectives, with equal respect for each person involved. Once the emotional and ideological influences on the process are respected and resolved, the logistics of accountably resolving the matter may be more efficiently handled with mutual satisfaction.

- Focus on what is most important to all involved; promote listening with replay of main points.

- Define specific behaviors that caused harm, and their effects.

- Hold people responsible for their actions, feelings, thoughts, and boundaries.

- Include respect for the value of different kinds of needs, with equanimity and fair regard for all.

- Use kind words, gestures, postures, a talking stick, and tools and processes such as those described in Part III.

- Allow expression of feelings and unmet needs, with clear boundaries.

- Take stock of existing and formative agreements and goals.

- Welcome requests for actions to satisfy needs.

- Ensure that everyone involved has spoken and feels heard.

- Brainstorm actions that resolve issues and prevent future harm.

- Let individuals volunteer to take specific rectifying actions.

- Establish trusted means of accountability and ongoing on- and off-line communication.

- Create doable agreements among those taking responsibility for immediate and future actions.

- Confirm ongoing support and involvement within broader communities.

Emulate Successful Community Models

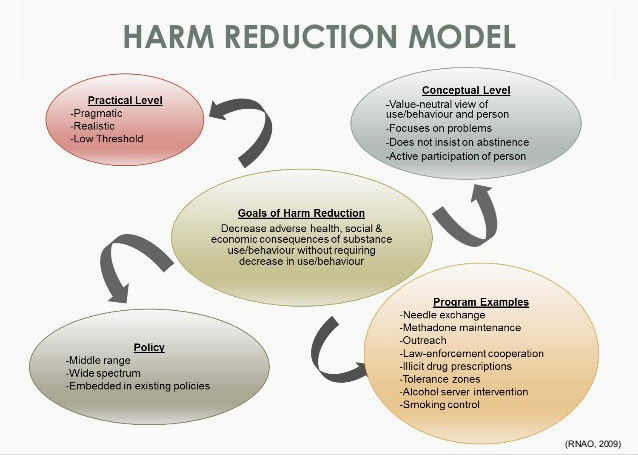

Harm Reduction

From a medical or spiritual view, when harm falls on a member of community, the entire community is affected; and when communities respond to harm with mercy, the entire community benefits. Examples of shared responsibility in community, such as Ho’onoponopono and traditional tribal circles in North America, began with relatively small clans. We must evolve these systems to serve today’s larger communities.

We know that awareness and civil action can shift paradigms to improve public health and well-being, as with efforts to reduce smoking and littering, and to increase seat belt use, as well as with LGBTQ and women’s empowerment. A merciful community response for community health extends caring for even the most vulnerable or desperate individuals. A merciful drug policy, for example, lessens harm in intravenous drug addiction, as shown in the diagram below.

Restorative Circles

Restorative circles are another successful model of mercy in community. These circles support mutually respectful dialogue among the “three parties to a conflict” – those who have acted, those directly impacted by a focus, and the wider community. Participants invite each other and attend voluntarily. The dialogue process used is shared openly with all participants, and guided by a community member. The process ends when actions have been found that bring mutual benefit.

Since merciful systems are interwoven with accountability and responsibility, they bring out the best in people. Even those of us raised with “dog eat dog” attitudes often willingly, even gratefully, follow steps to do right for those we have hurt. The payoff is dignity, a clean slate, and the opportunity to make good on a past mistake. Individuals and the entire community are regenerated through merciful processes.

For more information on restorative justice and truth and reconciliation, see Chapter 28, Section 4 of the Community Tool Box, on Forgiveness and Reconciliation.

Kids who act out at school are doing the best they can to cope with huge stress. Positive behavioral methods that are not punitive and that keep kids in class have proved to create a safer environment at almost 30,000 schools in the U.S.. Rather than deny education to troubled children, the recipe is to keep teaching them and acknowledge their progress with positive feedback.

Workplace Cooperatives

Mercy at the workplace means some sort of cooperative, shared ownership experiment, as with Tucson’s local Food Conspiracy. Shoppers easily become members, so that “Do you carry tofu?” turns into “Did we get any fresh tofu today?” Workplaces, like all communities of people, co-create merciful solutions through the three virtues.

Mercy as a Way of Life: L’Arche

In the community called L’Arche, in rural France, inhabitants take co-responsibility for errors that they, personally, didn’t create. To maintain discipline in the community without coercion, the Companions used the system of responsibility and co-responsibility.

“Responsibility” in this group means that we take responsibility for our own mis-deeds, whether anyone knows about them or not. If someone does notice our mistakes, and we don’t make amends ourselves, that’s when “co-responsibility” comes into play. The witness takes co-responsibility to approach us, the offenders, in private, and point out our faults. If we refuse to admit we did anything wrong and our accuser remains convinced, the accuser takes on the work we failed to do and makes amends, or otherwise volunteers to be the one accountable for wrong done. Generally, the offender then recognizes the fault and fulfills the promise of mercy.

Organize around Meeting Needs, Issues, and Methods

The merciful practices above, and the following structures below, help groups serve each other and others gracefully in their processes of organization and outreach as well as in deliberation, decision making, and follow-through.

- Hold house meetings to discuss urgent community issues and possible community projects.

- Form teams to process decisions and to inform others about them.

- Make participation inclusive.

- Set up communication structures and processes.

- Create support and discussion groups.

- Set up outings to support all kinds of people.

- Approach schools, theaters, art and dance studios.

- Write poetry and songs to comfort children and elders.

- Plan fun events with unusual coalitions.

- Offer to share communication methods with other groups; see Part III.

- Listen to lonely and marginalized people.

- Create pamphlets, songs, guerilla art, and street theatre.

- Make, sell, and wear T-shirts with merciful messaging.

- Offer Open Space events for community member to self-organize and develop their own agendas.

- Join or start a group that practices nonviolent and emotionally supportive communication skills. Bring those skills to schools, workplaces, neighborhoods, public servants, and places of worship – and especially to those settings steeped in violent cultures.

- Encourage civic deliberations, assemblies, and discussion groups that reach out for diversity and inclusivity; support their action commitments.

- Break up large groups into smaller assemblies, in order to collect and include democratic input more efficiently,

- Organize issue-based community calendar initiatives, or start your own.

Part III: Merciful Communication Methods

“Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and right doing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.”

— Rumi

The three virtues of mercy, described in Part I and elaborated within Part II, are here joined with methods that help transform these virtues into actions that solve problems. This last part of our mercy section is a sampler of ways that the authors of this paper have seen compassionate communication practiced in our own community, Tucson, Arizona. For example, our local Information Exchange fosters understanding, forgiveness, and accountable action, and gives a foothold for mercy to unfold.

Mercy may arrive without any communication technique or process; there is no prescription. The following techniques are rather offered here as guide rails when human interactions would otherwise go off track or crash. These specific structures have proven to be valuable to help open hearts and minds for people to feel comfortable to express, and process, what is important to be enacted upon by others. Follow the links below to learn more about these tools and connect with groups to practice kind communication together.

There are three steps in merciful communication, which reflect the virtues of understanding, forgiveness, and accountability:

- Take turns speaking on one point at a time, and be precise with facts.

- Feel the emotional repercussions of the harm done from different points of view.

- Move from expression of regrets to agreements for making amends.

Traditional Council Practices

We are grateful for First Nations cultures who demonstrate the logistics of mercy. Great Plains and other traditional councils create and protect space for people to speak and listen. The structure is established on a foundation of honesty, connection, and respect. Traditional councils typical begin with invoking humble gratitude for the wisdom of those who have come before, frequently with the invocation, “all my relations.”

Circles